Online Course Development: A Practical Guide to Designing Effective Digital Learning

Online course development is often misunderstood as simply recording videos or uploading content to a platform. In reality, it’s a structured learning design process that shapes how people learn, engage with material, and apply new knowledge. Whether you’re moving workplace training online, developing vocational programs, or creating professional development courses, understanding this process makes the difference between courses that work and courses that don’t.

This guide focuses on the design decisions that create effective digital learning experiences. We’re not discussing which platforms to use or how to monetize content—we’re exploring how to design online learning that actually achieves its purpose.

What Is Online Course Development?

Online course development is the process of designing, building, and refining digital learning experiences that help people achieve specific learning outcomes. It’s fundamentally about learning design, not technical production.

This process differs from related activities that people often confuse with course development:

Content creation focuses on producing materials—writing, recording, or designing resources. Course development uses content strategically within a learning experience, but creating content isn’t the same as designing learning.

Video production is a delivery format. While videos can be valuable learning tools, producing videos isn’t course development. Many effective online courses use minimal video, while some video-heavy courses fail because they prioritize production over learning design.

Platform setup involves choosing and configuring technology. Platforms deliver courses, but they don’t design them. The best platform in the world can’t fix a poorly designed course.

Why does this distinction matter? Because design quality directly impacts whether people actually learn. Well-designed courses keep learners engaged, help them understand and apply new knowledge, and achieve measurable outcomes. Poorly designed courses—no matter how polished the videos or sophisticated the platform—result in dropout, frustration, and wasted time.

The Core Stages of Online Course Development

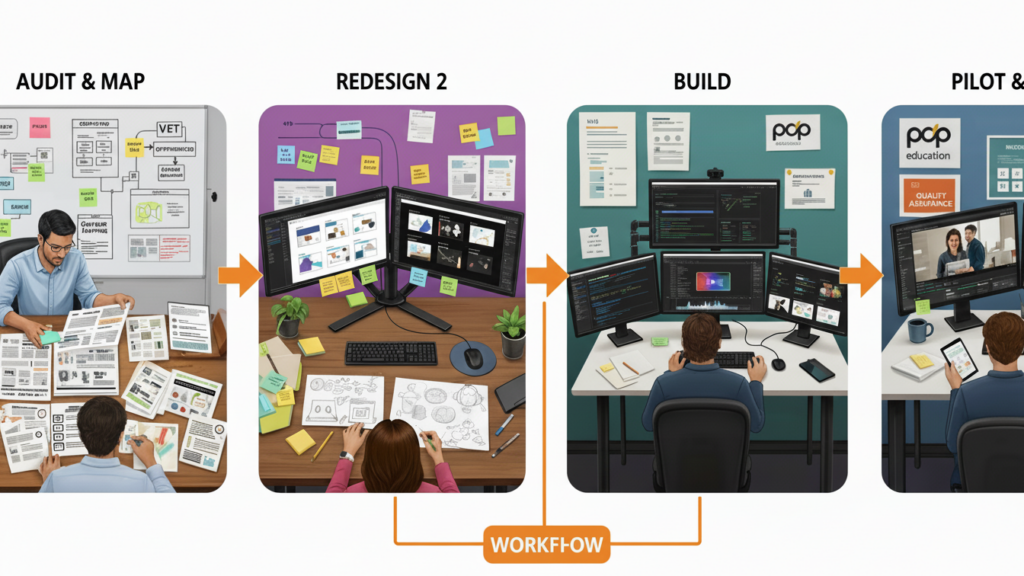

Effective online course development follows a structured process. These stages overlap and iterate, but each addresses essential design decisions.

Learner and Context Analysis

Before designing anything, understand who will take the course and why. What do they already know? What gaps are they trying to fill? What constraints affect their learning—time availability, access to technology, workplace context? What motivates them to complete the course?

This analysis shapes every subsequent decision. A course for experienced professionals looks completely different from one for newcomers. Learners with 15 minutes a day require different design than those with dedicated study time.

Defining Learning Objectives and Outcomes

Clear objectives state exactly what learners should be able to do after completing the course. These aren’t vague hopes like “understand project management”—they’re specific, measurable outcomes like “develop a project plan with defined milestones and resource requirements.”

Learning outcomes drive everything else. They determine what content is necessary, what activities learners need, and how you’ll know learning happened. Without clear outcomes, course development becomes content dumping without purpose.

Course Structure and Sequencing

Structure determines how learning builds over time. What needs to be understood before tackling more complex concepts? How do individual lessons connect into a coherent learning journey? Where do learners practice applying knowledge before being assessed?

Good sequencing supports learning by introducing concepts in logical order, providing practice before assessment, and creating clear pathways through material. Poor sequencing leaves learners confused about why they’re learning things or struggling with concepts they weren’t prepared for.

Content and Learning Activity Design

This is where most people think course development begins, but notice it comes after analysis, objectives, and structure. Content design means deciding what information, examples, and explanations learners need. Activity design means creating opportunities to practice, apply, explore, and engage with material.

Online courses aren’t just information delivery systems. Effective design balances content with activities—discussions, problem-solving tasks, scenario analysis, reflection exercises—that help learners process and apply what they’re learning.

Assessment and Feedback Design

Assessment shows whether learners achieved the outcomes you defined earlier. It might involve quizzes, projects, practical demonstrations, or peer review—whatever actually measures whether someone can do what the course promised they’d learn.

Feedback helps learners understand their progress and improve. In online environments where immediate instructor feedback isn’t always possible, design must build in feedback mechanisms—automated responses, model answers, peer review, or scheduled instructor check-ins.

Technology and Delivery Considerations

Now you consider how technology supports your design. What platform features do you need—discussion forums, assignment submission, video hosting? How will learners access the course—computers, mobile devices? What technical skills can you assume?

Technology decisions should support your design, not drive it. Choosing a platform first, then trying to fit your design into its constraints, usually results in compromised learning experiences.

Review, Evaluation, and Iteration

Courses improve through testing and refinement. This might mean piloting with a small group, gathering feedback, analyzing completion data, and revising content or activities that aren’t working. Online courses aren’t built once and left alone—they evolve based on how real learners engage with them.

Designing Online Courses for Adult Learners

Most online courses target adult learners—professionals seeking new skills, workers completing required training, or people advancing their careers. Adults learn differently from children, and these differences should shape design decisions.

Adults need relevance. They want to know immediately how learning applies to their work or goals. Generic examples or theoretical content without clear application loses engagement quickly. Design should connect learning to real situations adults face, using workplace scenarios, industry-specific examples, and practical applications.

Adults value autonomy. They appreciate having some control over their learning—choosing which topics to explore in depth, determining when they study, or selecting which activities match their needs. While structure is important, rigid lock-step progression frustrates adult learners who have good reasons for wanting flexibility.

Adults bring experience. They’re not blank slates. They arrive with knowledge, skills, and perspectives from work and life. Good design acknowledges this by building on existing knowledge, creating opportunities for learners to share experience, and connecting new concepts to what they already understand.

Adults want practical outcomes. They’re learning to do something—perform better at work, qualify for new roles, solve specific problems. Assessment and activities should focus on practical application, not just knowledge recall. If you can’t show how learning leads to improved performance or capability, adult learners question its value.

Online Course Development Methods and Formats

Different course formats serve different purposes and learner needs. These are design choices, not trends to follow.

Self-paced courses let learners progress independently on their own schedule. They work well when flexibility is essential, when learners have varied starting knowledge, or when content doesn’t require real-time interaction. The trade-off is less peer interaction and greater risk of dropout without external accountability.

Cohort-based courses move groups through content together, often with scheduled sessions and group activities. They create community, enable peer learning, and provide accountability through shared timelines. They require coordination and work less well for learners with unpredictable schedules.

Microlearning delivers content in short, focused segments—typically 5-10 minutes—each addressing one specific outcome. It suits busy professionals, works well for reference and refresher learning, and integrates easily into workflow. It’s less appropriate for complex topics requiring sustained engagement.

Long-form programs take weeks or months and develop substantial knowledge and skills. They support deeper learning, complex skill development, and significant capability building. They require sustained commitment and careful design to maintain engagement over time.

Blended delivery combines online and face-to-face elements. Online components might deliver content and enable flexible practice, while face-to-face sessions focus on application, coaching, or complex discussion. This approach balances flexibility with high-touch support but requires coordinating multiple delivery modes.

Scenario-based and simulation-based learning uses realistic situations or simulated environments where learners make decisions and see consequences. These formats excel at developing judgment, problem-solving, and application skills in safe practice environments.

The right format depends on learning outcomes, learner context, and available resources. Don’t choose based on what’s currently popular—choose based on what serves your learners and objectives.

Common Mistakes in Online Course Development

Understanding common pitfalls helps avoid them in your own development work.

Content overload happens when designers try to include everything they know about a topic. More content doesn’t create better learning—it creates overwhelmed learners. Good design focuses ruthlessly on what’s necessary to achieve defined outcomes, cutting everything else.

Tool-first design starts by choosing a platform or loving a particular technology, then trying to build learning around it. This backwards approach constrains design unnecessarily. Start with learning needs, then find tools that support them.

Misalignment between objectives and assessment occurs when learning objectives promise one thing, but assessment measures something else. If objectives focus on practical application, assessment can’t be multiple-choice recall questions. Every assessment task should directly measure stated outcomes.

Passive learning experiences treat courses as information delivery—watch videos, read content, take a quiz. Adults need to actively engage with material through discussion, problem-solving, application, and reflection. Passive courses have high dropout and low retention.

Ignoring learner context means designing without understanding actual learner situations. Assuming full-time study availability when learners are working full-time, requiring synchronous participation across time zones, or demanding technology learners don’t have access to—all create barriers that design should address, not ignore.

Building In-House vs Working With Specialists

Organizations developing online courses face a decision about capability. Should you build courses internally or work with learning design specialists?

Internal capability matters. Do you have staff with instructional design expertise, not just subject knowledge? Can they dedicate time to development without compromising other responsibilities? Online course development requires different skills than teaching or training face-to-face.

Scale and complexity influence this decision. A simple compliance module might be manageable internally. A comprehensive qualification program with multiple courses, complex assessments, and various delivery modes likely benefits from specialist expertise.

Compliance and quality requirements affect the decision too. Courses requiring regulatory approval, formal assessment validation, or professional accreditation often need specialist support to meet standards. The stakes are higher, and mistakes are costlier.

Time and sustainability are practical considerations. How quickly do you need courses ready? Can you maintain and update them long-term? Initial development is only the start—courses need ongoing revision, improvement, and updating as content changes or feedback emerges.

There’s no universally right answer. Some organizations successfully develop excellent courses internally. Others benefit from specialist support, particularly for complex or large-scale development. The key is realistic assessment of capability, resources, and requirements.

Why Good Online Course Development Matters

The difference between well-designed and poorly designed online courses isn’t cosmetic—it’s fundamental to whether learning actually happens.

Engagement depends on design. Learners stay engaged when courses are relevant, appropriately challenging, and actively involve them in learning. Poor design leads to quick dropout as learners realize the course won’t deliver value worth their time.

Completion and retention connect directly to design quality. Courses with clear structure, manageable workload, and meaningful activities see higher completion. Learners remember and can apply what they learned from well-designed courses; poorly designed courses result in forgotten information and unusable knowledge.

Skill transfer—whether people can actually use what they learned—depends on design that emphasizes application, provides practice opportunities, and connects learning to real contexts. Courses focusing only on knowledge transmission rarely change what people can do.

Organizational outcomes matter when training has purpose beyond individual learning. Whether goals involve compliance, performance improvement, or capability building, poorly designed courses waste resources without achieving results. Good design produces measurable value.

Quality assurance becomes easier with strong design foundations. Well-designed courses have clear objectives, aligned assessment, and documented design rationale. This supports validation, audit, and continuous improvement processes.

Conclusion

Online course development is intentional learning design, not content creation or technology setup. Effective digital learning emerges from understanding learners, defining clear outcomes, structuring learning logically, designing engaging activities, and aligning assessment with objectives.

Tools and platforms support good design—they don’t create it. The best technology can’t fix unclear objectives, poor sequencing, or passive learning experiences. Conversely, simple technology becomes powerful when it supports well-designed learning.

Effective online courses are planned, tested, and refined based on how real learners engage with them. They’re not rushed projects or converted PowerPoints. They’re carefully constructed learning experiences that respect adult learners, achieve defined outcomes, and produce measurable results.

Whether you’re developing your first online course or improving existing programs, focus on design decisions that serve learners and outcomes. That’s what transforms content into learning.